York research team removes harmful waste from Canada’s groundwater

Tags:

This story originally appeared on YFile.

An internationally recognized leader in the development of novel green technologies, Professor Satinder Kaur Brar, Lassonde School of Engineering, is on a mission to add value to residues and remove toxic compounds from the environment that pose extreme hazards to ecological and human health.

Brar’s research hinges on two main themes: the removal of emerging contaminants such as plastics, chemical antibiotics, and pesticides from wastewater and drinking supply water; and value-addition of wastes.

“Residues are everywhere in the environment. My research aims to harness this waste through biotechnical approaches to create something of higher value that will have a positive impact on the environment,” says Brar, the James and Joanne Love Chair in Environmental Engineering at York University.

Her current Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC)- and Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI)-funded research is developing an enzyme-based technology for emerging contaminants. Brar and her team, which includes four PhD students, were successful in removing petroleum hydrocarbons, a naturally occurring chemical that presents in crude oil, petroleum-based fuels and lubricant oils, from groundwater.

The research has significant implications for Canada’s oil and gas industry, of which Canada is a top producer and exporter. In 2022, the Government of Canada committed $1.16 billion to clean up and remediate 23,900 sites contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons, monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. The chemicals are dangerous because they can move through the soil to air or water, creating odours and impairing soil processes such as water retention and nutrient cycling. Human consumption of the toxin can lead to serious health repercussions and can damage the immune system, kidneys, liver and other organs.

Brar is working with a geochemist named Richard Martel at the Institut National de la Recherche Scientific (INRS) and TechnoRem Inc., an engineering consulting firm in groundwater remediation. The team is leveraging the enzymes of microorganisms identified in petroleum hydrocarbons to accelerate the rate of chemical reaction. The application results in the degradation of petroleum compounds by reducing the activation energy for a particular reaction.

“Enzymes are tools in the hands of microorganisms and can help degrade contaminants in the soil,” says Brar.

Using enzymes instead of microorganisms means the team can degrade the targeted compound without any previous adaptation to the soil matrix.

“Working with microorganisms means you’re injecting a live species into an environment. Enzymes, on the contrary, that are not consumed, degrade after a period so it doesn’t cause any harm to the surrounding environment,” she says.

The next stages for the research, which initially kicked off in 2014, is to test the enzymes in situ at petroleum sites in northern Canada and the Arctic.

“Low temperatures impact the efficiency of treatment, but we have isolated the cold-active enzymes which can be active in cold conditions,” she says.

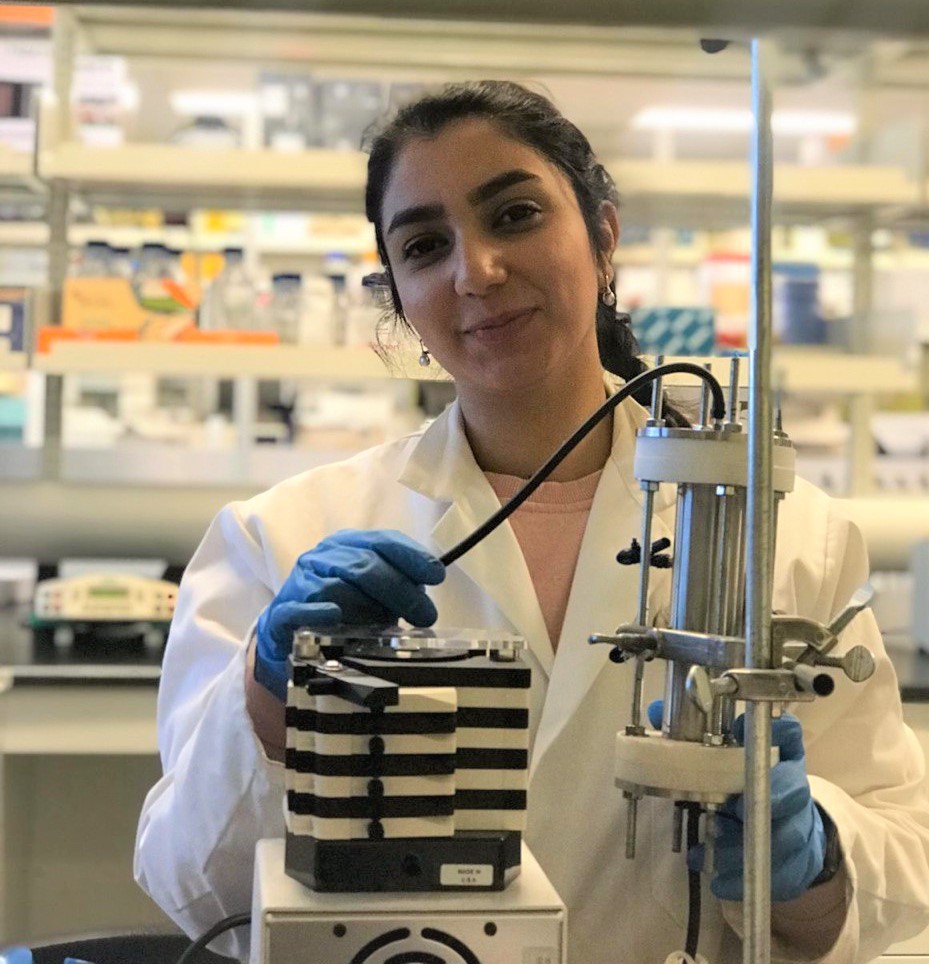

Saba Miri, a fourth-year PhD student in civil engineering and environmental engineering, says that cold enzymes are safer for the environment and for humans. “If they do make their way into the drinking water, they won’t harm human health,” she says.

“The next step is to adapt our solution to industry so that we have greener, safer technologies,” says Miri who aspires to remain on the project after she graduates. “Petroleum hydrocarbons can and do leak into the groundwater, which is a main source of drinking water for many remote communities in Canada, including many Indigenous communities. Our research aims to protect these communities with innovative technology.”

A chemist at heart

When Brar was pursuing a master’s in organic chemistry, she was curious about the amount of chemicals used in synthetics and toxic solvents. She wanted to know where they went. Her search for answers led her to pursue a master’s in environmental engineering, where she worked in remediation of organic solvents in the textile industry.

Her career led her to work in India as a defence research scientist spearheading an environmental project on building up explosive contaminants database. “It was a new area of research at a time where defence research was mainly focused on making better explosives and ammunition,” she says.

Brar later went on to complete her PhD in biochemical engineering in Canada at Quebec City. Ever since, she has worked on projects with industry and government, including a collaboration with Hydro Quebec to investigate the use of the biopesticides on the spruce budworm that led to deforestation and defoliation. Her research has also intersected with the health sector, measuring the pharmaceuticals that make their way into wastewater through urine.

“Municipal wastewater is a complex cocktail of what we, as a society, put in there,” she says, adding that “toxins don’t just disappear into thin air, they are usually transformed into something else.

“In my heart I am a chemist,” she explains. “That lens has helped me understand and unravel so many mysteries related to environmental science and the adverse impact of chemicals. There is a direct cause and effect relationship between chemicals and the ecosystem in the environment.

“Research can help instil respect for the environment which is still somehow neglected. I love that our research could potentially act as a driver for better environmental policies and laws,” says Brar.